My New Year’s resolution for 2017 is to get back to blogging regularly. So, here we go with John Ford’s hymn to the moral courage and human decency of the martyred American leader who steered our nation in the direction of justice.

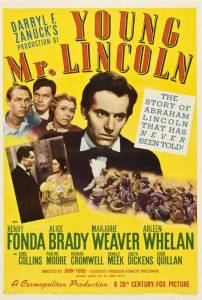

Henry Fonda almost didn’t take the role when Ford  offered it to him. He held Lincoln in such reverence, he said, that it would have been like “portraying Christ himself on film.” But Young Mr. Lincoln (1939) aims to show the great man before he was great, warts and all. (In fact, between the nose and the wart, it took three hours in make-up to get Fonda looking the part.) Honest Abe was not above cheating in the Fourth of July tug-of-war to help his team win. That self-deprecating humor of his may have disarmed dull-witted Midwesterners, but we in the audience recognize a skillful manipulator when we see one.

offered it to him. He held Lincoln in such reverence, he said, that it would have been like “portraying Christ himself on film.” But Young Mr. Lincoln (1939) aims to show the great man before he was great, warts and all. (In fact, between the nose and the wart, it took three hours in make-up to get Fonda looking the part.) Honest Abe was not above cheating in the Fourth of July tug-of-war to help his team win. That self-deprecating humor of his may have disarmed dull-witted Midwesterners, but we in the audience recognize a skillful manipulator when we see one.

Abe was way smarter than the townspeople of Springfield, Illinois—smart enough to know that intelligence scares people. Better to hide your light under a bushel. But make no mistake about it: Abe’s light shines forth for all to see. Even as a young man, Lincoln was guided by his conscience, not by self-interest. When he rescues two brothers falsely-accused of murder from a lynch mob, it’s clear that he is dedicated to a higher purpose.

We seem to lose our heads in times like this. We do things together that we’d be mighty ashamed to do by ourselves!

Lynchings were all too common in the Jim Crow South. In the 1930s, when John Ford was making this picture, the trials of the “Scottsboro Boys” drew attention to the issue of racial bias in the American legal system. Nine black teenagers were accused in 1931, on flimsy evidence, of raping two white women. The case dragged on for seven years, going all the way up to the Supreme Court, and became known in left-wing circles as “the case of The White People of Alabama vs. The Rest of the World.” Blues musician Lead Belly even wrote a song about the Scottsboro Boys.

There are clear parallels between the righteous Alabama Judge James Horton, whom newspapers at the time described as looking like “Lincoln without the beard,” and young Lincoln’s defense of the two brothers.

Judge Horton sacrificed his own career to see justice done, setting aside the guilty verdict reached by the all-white jury and calling for a new trial after he became convinced that the chief witness to the alleged crime was lying. It didn’t help. Fonda’s Lincoln has no beard. While his own legal career is at stake, Abe succeeds in catching out the chief witness in the boys’ case in a “crude, cold-blooded lie.” Hollywood being Hollywood, the perpetrator admits to lying and justice prevails.

I’m glad to see you return to writing your responses to films, Lisa. My only wish is that they were longer. Here, I wonder what period the film covers, where it leaves off, and also whether it was well received.

Now is probably a good time to be thinking of Lincoln, but then it may always be a good time to be thinking of Lincoln. The quotation you’ve chosen, though, seems particularly apropos.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, John. There were good reasons to be thinking of Lincoln in the 1930s, as I suggested in my review. The story was set in the 1830s, and there was a fair amount of foreshadowing to the Civil War, particularly at the end. The reviews were favorable — Henry Fonda’s performance was admired — and the screenplay was nominated for an Oscar, but Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washingtoncame out the same year, and fared better. I’ll be reviewing that one next.

LikeLike

Welcome back! I missed your reviews.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good to know I was missed. Happy New Year, Ellen.

LikeLike