True confession: I’ve seen some dogs with Cary Grant, but I never saw Charade. Maybe I was saving it for this past weekend, to cheer me up while I recovered from my second COVID booster. A little jaunt to Paris with the lovely Audrey Hepburn modeling a succession of elegant coat dresses and pillbox hats, and those oversized sunglasses that helped define the Holly Golightly look (along with the little black dress), capped off by the mature Cary in a playful mood, turned out to be just the ticket.

I settled down on the sofa with a cup of tea and was instantly drawn in, what with the jazzy, syncopated Henri Mancini score playing behind the titles designed by the great Maurice Binder, of James Bond fame. But then I got distracted. Walter Mathau’s, James Coburn’s and George Kennedy’s names spun by. I didn’t know those guys were in Charade!

Kennedy had only recently left the service, having enlisted in 1943, served under Patton in the infantry, earned two Bronze Stars in the Battle of the Bulge, then up and reenlisted when the war ended. “Herman Scobie,” a ruthless guy with a short fuse who had a hook instead of a right hand was an early role for him. 1967 would be his big year: The Dirty Dozen and Cool Hand Luke both came out. He won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor for his performance as “Dragline” in the latter. (Little-know others in that movie, since we’re playing the game: Dennis Hopper as “Babalugats,” Wayne Rogers as “Gambler”, Harry Dean Stanton as “Tramp”).

Mathau seemed to be in a bad-guy phase, movie-wise. He used a whip on Burt Lancaster in The Kentuckian (1955) and got beaten up by Elvis Presley in King Creole (1958). Knowing him as Oscar Madison, though, I wouldn’t have believed he was a fake spy—I mean agent—were it not for the suspicious mustache. He had yet to grow into a loveable curmudgeon.

Coburn was close to the peak of his career, coming off The Magnificent Seven (1960) and The Great Escape (1963) when he made Charade. But for a bad decision, he could have kept riding that wave; Sergio Leone wanted him for Fistful of Dollars, but Coburn asked for too much money and the role went to a lesser-known actor, Clint Eastwood.

But who’s that balding little guy with him? The name Ned Glass meant nothing to me, but “Leopold W. Gideon” sure looked familiar. Turns out he was a character actor who played in a number of shows and movies I watched growing up, including Get Smart, Hogan’s Heroes, The Monkees and Julia (he was nominated for an Emmy for one episode of that show). His big breakthrough came with West Side Story (1961), where he played “Doc.” Before that, he played a series of uncredited parts in movies with titles like I’m from Missouri (1939), Callaway went Thataway (1951) and Stop, You’re Killing Me (1952). North by Northwest (1959) where he played the uncredited role of the ticket collector, broke that streak.

Grant and Hepburn were entertaining enough, I enjoyed the costumes and the scenery, but it’s the minor characters who kept me watching.

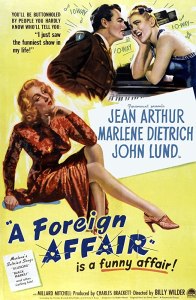

looking for fräuleins, prim Iowa congresswoman Jean Arthur attempting to ward off her would-be seducer’s (John Lund) advances by opening one file cabinet drawer after another and, when finally cornered for a kiss, reciting “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere” in a valiant effort to quell her own passion.

looking for fräuleins, prim Iowa congresswoman Jean Arthur attempting to ward off her would-be seducer’s (John Lund) advances by opening one file cabinet drawer after another and, when finally cornered for a kiss, reciting “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere” in a valiant effort to quell her own passion. of the bombed-out German capital from the congresswoman’s plane, and seen various characters picking theie way through the rubble at night. Still, we’re unprepared for the bitterness that undercuts the jaunty tune of

of the bombed-out German capital from the congresswoman’s plane, and seen various characters picking theie way through the rubble at night. Still, we’re unprepared for the bitterness that undercuts the jaunty tune of

That’s got a lot to do with the director, George Marshall, who went from making traditional Westerns during the Silent era to making comedies with Laurel and Hardy (among others) in the 1930s. Here he assembles a quirky cast, actors you wouldn’t expect to see in the same picture.

That’s got a lot to do with the director, George Marshall, who went from making traditional Westerns during the Silent era to making comedies with Laurel and Hardy (among others) in the 1930s. Here he assembles a quirky cast, actors you wouldn’t expect to see in the same picture. Marshall makes this ensemble piece sparkle. I like Jimmy Stewart’s folksy sheriff’s deputy better than the congressman he went on to play that same year in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. He’s less uptight, succumbing to Frenchy, surprising himself, and you like him better for it. Supposedly the two stars had a brief romance on the set. Nobody could resist Dietrich.

Marshall makes this ensemble piece sparkle. I like Jimmy Stewart’s folksy sheriff’s deputy better than the congressman he went on to play that same year in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. He’s less uptight, succumbing to Frenchy, surprising himself, and you like him better for it. Supposedly the two stars had a brief romance on the set. Nobody could resist Dietrich.

She’s too high-principled to steal him away from her sister — nobody does high-principled better than Hepburn — even though we can see that she’s just his type.

She’s too high-principled to steal him away from her sister — nobody does high-principled better than Hepburn — even though we can see that she’s just his type. Here he is, being arrested by the standard-issue secret police agents in their leather trench coats following the disastrous opening of his Great Socialist Fun Park.

Here he is, being arrested by the standard-issue secret police agents in their leather trench coats following the disastrous opening of his Great Socialist Fun Park. and Admiral Lord Horatio D’Ascoyne, followed by General Lord Rutherford, who is felled by an exploding jar of Beluga caviar. “Used to get a lot of this stuff in the crimea. One thing the Russkies do really well.”

and Admiral Lord Horatio D’Ascoyne, followed by General Lord Rutherford, who is felled by an exploding jar of Beluga caviar. “Used to get a lot of this stuff in the crimea. One thing the Russkies do really well.”