I recently listened to Sissy Spacek’s narration of To Kill a Mockingbird, which was simply wonderful. We’d been assigned the novel in a ninth grade English class—not the ideal circumstances for encountering a work of literature.  Laboriously, we dissected the book’s message, extracting solemn truths like that line of Atticus’s: “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view … until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.”

Laboriously, we dissected the book’s message, extracting solemn truths like that line of Atticus’s: “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view … until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.”

The injustice of a white jury in Alabama convicting a black man, Tom Robinson, on false evidence for the crime of raping a white female was awful, but not surprising. I was more shocked when Bob Ewell attacked Jem and Scout. It was 1970 and George Wallace was running an ugly, racist campaign for governor of Alabama. Calling his opponent names, showing ads depicting a white girl surrounded by seven black boys alongside the slogan, “Wake Up Alabama!” He won the election in a landslide and entered the presidential race the day after his victory, gaining momentum in the primaries until an assassination attempt forced him to withdraw.

No, Tom Robinson’s conviction was expected, and I didn’t need to have all of Harper Lee’s foreshadowing pointed out to me by my English teacher. I knew what was coming.

“Atticus—” said Jem bleakly.

He turned in the doorway. “What, son?”

“How could they do it, how could they?”

“I don’t know, but they did it. They’ve done it before and they did it tonight and they’ll do it again and when they do it—seems that only children weep. Good night.”

I’m more inclined to weep now than I was at fourteen. Watching the film the other night, I was devastated when Robinson looks at Atticus as he is being led out of the courtroom, after the verdict has been read. I told you so, his look seems to say. It’s almost as if he blames Atticus for giving him grounds for hope. Nothing would change in Macomb County, Alabama. Only a fool would believe otherwise.

This confrontation is not in the book, by the way. Later, when Atticus learns that Robinson has been shot dead while attempting to escape from prison, Lee allows him a moment of insight, a fleeting acknowledgment that he, and white America, failed to provide justice for all. They were going to appeal the verdict; Atticus had faith that in the courts, all men are created equal.

“We had such a good chance,” he said. “I told him what I thought, but I couldn’t in truth say that we had more than a good chance. I guess Tom was tired of white men’s chances and preferred to take his own.”

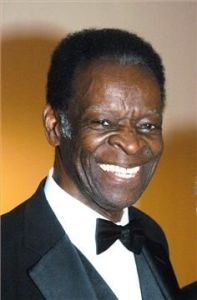

Brock Peters, the actor who portrayed Robinson,  conveyed his hopelessness so powerfully. In a documentary on the making of the film, Fearful Symmetry (included with the 50th Anniversary Edition DVD), Peters speaks of his own experience with racism:

conveyed his hopelessness so powerfully. In a documentary on the making of the film, Fearful Symmetry (included with the 50th Anniversary Edition DVD), Peters speaks of his own experience with racism:

“My life as an African American, or a black American, has had a lot of horror in terms of racism.” He pauses, hesitates before he uses the word, as if steeling himself to speak the truth. “I’ve been kicked, beaten. I’ve seen the worst of it. I guess I’ve been fortunate in being able to step back from the brink of an anger that would engulf me and cause my life to go in a really downward spiral.” Again he stops, choosing his words with care. “The anger, the frustration, the isolation that one could experience and often did experience was an easy place for me to get to, to tap, to use in my performance.”

I’m not sure that movie audiences in 1962 picked up on these emotions. Bosley Crowther’s review in the New York Times speaks of childhood joy and wonder and close family relationships in the picture (you wonder if he read the book) but only alludes to “the trial scene” and “good and evil” as major events or themes. Reviewers of Lee’s novel could be equally obtuse. The Atlantic called it “hammock reading” and reassured readers that, despite the main action (“a Negro accused of raping a white girl”), “none of it is painful, for Scout and Jem are happy children, brought up with angelic cleverness by their father and his old Negro housekeeper. Nothing fazes them much or long.”

I certainly see more now than I did as a ninth grader. Here we are, having traveled a long way since the era of Jim Crow and the early days of the Civil Rights Era, only to find ourselves back in Macomb County, Alabama.

Your conclusion—”Here we are,…back in Macomb County”—may be the most striking part of your commentary. White America seems, since the 60s, to have gone looking for more objects of resentment and fear, as if inventing new enemies (to adapt a phrase used by Umberto Eco) were a necessity of our way of thought, and we’ve had no trouble finding them. Those of us who’ve managed to shed this attitude (it seeped into me when I was a child) or who sensed it but never adopted it can be glad for the voices of artists such as Harper Lee and the makers of this film, but the artists sometimes suffer too. It’s clear from what you quote here that Brock Peters did. I learned just yesterday of another instance. To quote the opening of a Times report from a few days ago, “The Iranian director Asghar Farhadi, whose film ‘The Salesman’ is nominated for an Academy Award for best foreign-language movie, said on Sunday that he would not attend the Oscars ceremony next month even if he were granted an exception to President Trump’s visa ban for citizens from Iran and several other predominantly Muslim countries.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good for Asghar Farhadi. I do think that artists have a responsibility to stand up in times like these. I look to James Baldwin as a model here, because he took a stand in public, yet remained generous in his understanding of his fellow humans, resisted the moral high ground, the lecturing, in favor of a more complex world view. Most of all, he plumbed his own depths, exposed his soul, admitted his weaknesses. I’m very much looking forward to seeing I Am Not Your Negro.

LikeLike